We first met Amina just after dawn on a windy January morning in Jama’a, Kaduna State. Knee‑deep in tomato vines, she harvested fast, hoping to reach the local market before the midday heat wilted her crates. By month‑end she made only ₦35,000 in profit, and even that came after spoilage deductions and bruising negotiations with middlemen.

Everything shifted one ordinary Thursday when a CoAmana field agent unfolded a plastic table beside the okra sellers. Curious, Amina handed over her cracked Itel phone. Ten minutes later her profile was live on Amana Market and before sundown, a buyer in Abuja had reserved 80 kg of tomatoes on buy‑now‑pay‑later (BNPL) terms. She tucked her phone beneath her hijab so she could feel each new‑order vibration against her collarbone.

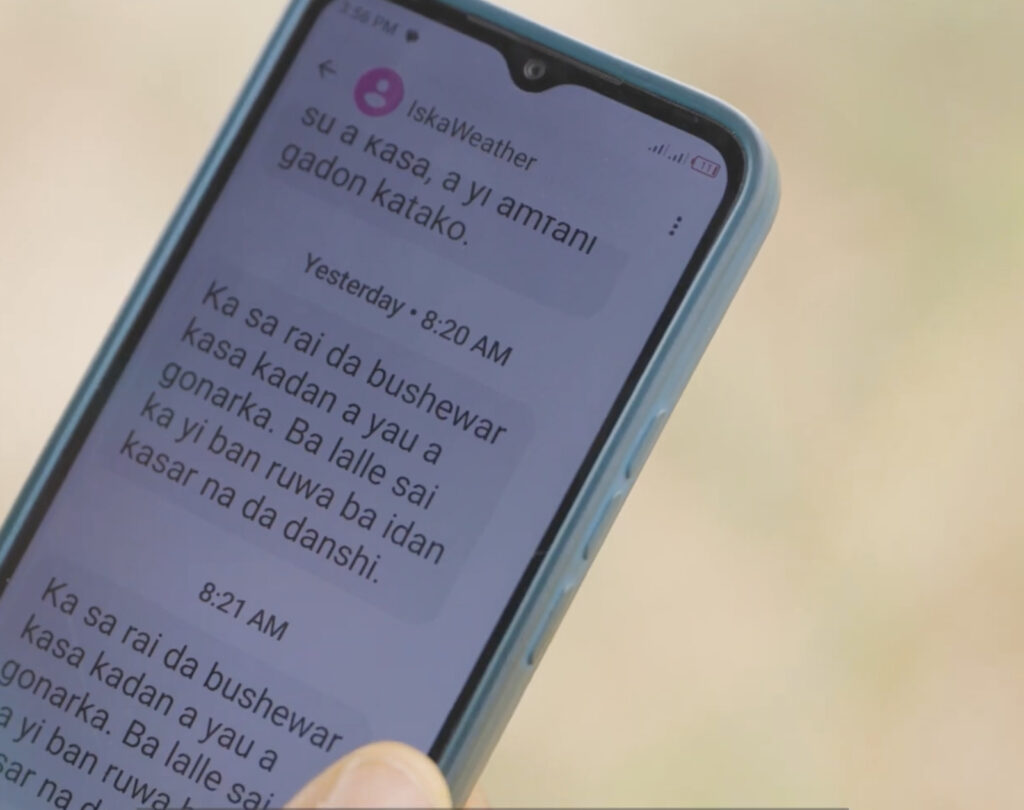

April tested Amina and the system. A black‑sky storm barreled toward Jama’a, and at 05:14 an SMS advisory warned: “Heavy rainfall in 24 h. Harvest early.” Amina roused her children; by breakfast they’d trucked 150 kg of produce to an AFEX warehouse in Kafanchan. When the downpour finally pounded tin roofs, every tomato sat dry behind warehouse doors. Losses: <20 kg.

With storage secured, Amina learned a new game: timing. March prices bounced between ₦300 and ₦450 per kilo, but she released stock in three waves, averaging ₦530/kg, an 18 % premium that bankrolled sacks of ginger for the next planting. That was not the last challenge April brought her way. A battle with malaria mean that Amina could not conduct business for a few days, leading to loss of products that she could not pick up or store. An Advantage Health community health educator (CHE) logged symptoms into the Amana app and filed a micro‑insurance claim on the mud veranda. Two hours later hospital fees were covered, plus a small payout that hired labour to keep shipments on time. “Illness used to stop my income,” she told me the next day, “now it pauses nothing.”

Amina was beginning to increase her earnings and require more capital to operate her business. But Capital without knowledge can be a challenge. Amina registered for the Jennifer Etuh Foundation financial literacy clinic. Women balanced notebooks on their knees, mapping cash-flow cycles and sketching vertical sack farms. Completing the course auto-raised Amina’s BNPL ceiling from ₦50,000 to ₦100,000 with a possibility for more increase, providing her with more capital for business operations

By June, evening light found her courtyard alive with neighbors. Eight women, drawn by her new motor‑pump and steady deliveries, sat in the dust uploading okra, ginger and millet onto Amana Market. Orders travelled 200 km to Abuja, and a quiet sisterhood economy bloomed.

By the Numbers

| Metric | January | July | Change |

| Monthly revenue | ₦120 k | ₦250 k | 2.1x |

| Monthly Profit | ₦35 k | ₦70k | 2× |

| Post‑harvest loss | 40 % | <15 % | ▼ 25 pp |

| Repeat‑buyer rate | 15 % | >35% | +20 pp |

| Insurance claims settled | — | 2 (≤2 h each) | New safety net |

Each element—digital storefront, weather intel, storage, insurance, training—works alone, but woven together they created what Amina now calls “talla mai kanshi”—perfumed trade—because nothing about it smells of panic. “Buyers compete for my tomatoes before the crates leave the warehouse,” she grins. “And my daughter’s school fees are paid before term begins.”

With 50 women in the pilot averaging a 4.8× revenue jump, CoAmana and partners will scale WEE to 2 500 women by 2027—expanding warehouses and doubling CHE routes.